A Practical Guide to Linux for Beginners

Things nobody will tell you about Linux when you're just getting started as a Windows user

Whether you can’t or won’t run Windows 11 and are looking for alternatives with Microsoft ending support for Windows 10 later this year, are ready to embrace the Year of the Linux Desktop™, or are simply looking to expand your horizons, there has never been a better time to make the switch to Linux. The word Linux still seems to conjure images of dimly lit basements and empty Mountain Dew cans - an operating system reserved for pasty nerds that is difficult to understand, even more to difficult to use, has no driver support for the hardware you want to use, and is overall a buggy mess which requires extensive knowledge of the command line interface in order to accomplish simple tasks. These were absolutely well-deserved criticisms in 2005, but fast forward 20 years, replace “command line interface” with “registry editor” and suddenly this is a description of the latest iteration of Windows.

Mature distributions like Ubuntu or some of its popular cousins like Linux Mint are entirely capable of providing a grandma-proof desktop experience in 2025 - that is, for the average person’s use case (mainly the ability to open a web browser in order to access email, youtube, shopping, social media, etc.) it is easier than ever to use Linux as a daily driver without ever touching the command line or having to know much of anything about how computers work. Valve has even made massive strides in recent years in bringing gaming to Linux with Proton and SteamOS (based on Arch Linux) which powers their Steam Deck.

That being said, much of the beauty of Linux comes from the power and freedom of choice the command line gives you, and if you’re just getting started with trying to learn Linux for work, school, or gaming purposes, you’re probably looking for a bit more information than how to open the browser.

The Current State of Things

Nearly every “getting started” guide for Linux out there goes something like this:

- Some obscure discussion about kernels, terminal emulators, release schedules, and other cryptic information that probably doesn’t mean anything to you at this point

- How to choose the right distribution based on the previous discussion

- How to install it

- A list of 50 million commands you should start typing immediately

- Consult the manual if you have problems

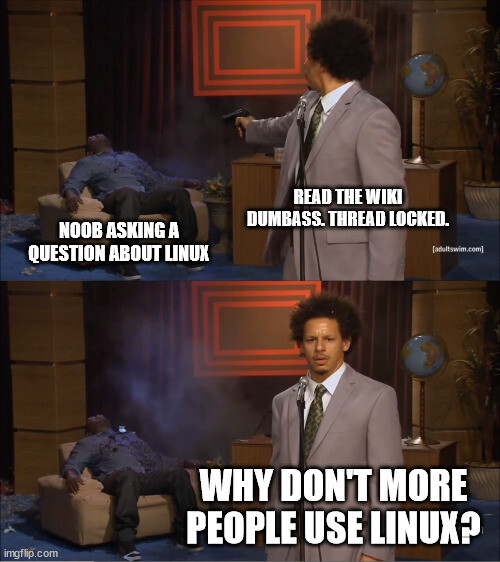

And then of course if you try to ask questions, you are almost guaranteed to get this response:

A wild Arch Linux user in his natural habitat

A wild Arch Linux user in his natural habitat

I’m not going to make any attempt to sway you towards any particular distribution or turn you into a professional command-line ninja in this article. There is no shortage of excellent reference material out there when it comes to these points above, but it seems some crucial context for really and truly getting started with Linux is always missing:

- Why are there so many options?

- Why can’t I install any programs?

- How do I do stuff?

This more or less sums up the new operating system vertigo I still remember feeling when I was first getting started. Linux is more than just a new set of desktop wallpapers and buttons, it’s a completely different way of thinking about what a computer is and how it should be used, which will more than likely require a bit of “un-learning” of the habits you developed when learning to use Windows. Hopefully once you find yourself staring at a freshly installed Linux desktop, you will be able to find answers to these most burning questions (or at the very least be able to form the basis of more specific questions) right away with the information presented here.

The Anatomy of a Linux Distribution (or “distro”)

So what exactly is a distro and why do you have to choose one? The thing is, Linux is really more of an idea than an operating system. I won’t get too deep into the open-source philosophy of Linux here, but I will make some rather large oversimplifications of it for the sake of understanding it (I promise this will be relevant shortly!)

Imagine that Microsoft is a car manufacturer instead of a tech company. They only produce one car model that anybody cares about, as well as all of the parts required to build it, and it’s called Windows. Every few years this model gets a facelift and maybe some new bells and whistles, but you more or less know what you’re going to get - a car with 4 wheels that works most of the time (hopefully). Linux, on the other hand, is just an engine, and a “Linux Distro” is an attempt to build a functioning car around that engine by attaching other useful components like a transmission, tires, seats, and so on and so forth. Unlike Windows, which comes complete with every part of the car being crafted by Microsoft, Linux is just what powers the car, and all the components are produced in a massively decentralized fashion by independent contributors with (generally) no affiliation to any corporate or government entity.

The nice thing about this decentralized production scheme is that all the components are built from the ground up with the idea that A) a component should do only one thing and do it well, and B) it should be easy to swap or modify that component later, because the blueprints for not just the overall car, but also all of its individual parts are available to anyone that wants them. So if you don’t like something about your car, you can simply remove that thing and replace it with a different one made by somebody else - or you can even make your own! Maybe you want a car with 3 wheels, or 28 wheels, or maybe you also want your car to be a boat; knock yourself out. Windows is almost the exact opposite of this. You cannot see the blueprints (closed-source), which means no one other than Microsoft can deeply understand how everything works behind the scenes, and as such, you more or less cannot make any modifications that Microsoft doesn’t want you to make.

Fun fact: The internet as we know it would probably cease to exist if it weren’t for some dude named Jeff thanklessly coding in his spare time

Fun fact: The internet as we know it would probably cease to exist if it weren’t for some dude named Jeff thanklessly coding in his spare time

Now, there are a metric shit-ton (that’s 2.55 standard shit-tons) of components required to build a car, and likewise probably even more software components that make up a Linux distro, but for the quick-and-dirty beginner’s guide I propose that there are really only 2 main software components worth thinking about, which comprise every modern distro (and also the main immediately observable differences between Linux and Windows):

- A desktop environment (that is, the “GUI”)

- A package manager

Here someone who is not a beginner might ask questions like “what about init systems? what about file systems? what about the windowing system? what about the shell? what about the network stack? what about the bootloader? what about the maintainers deciding to do XYZ differently from upstream? what about…” and to those people I say, this article is not for you 😎 Now let’s review these 2 major components:

Desktop Environments (DE)

This is almost certainly an unpopular opinion among Linux people, but it is mine nevertheless: the DE is probably the most important part of choosing a distro for beginners, because if you find the user interface is frustrating to use and you can’t use your computer to do computer things at all, you probably will have a hard time finding the motivation to learn how to do things in the terminal. Learning a new desktop environment is also going to be challenging at first, but much less so than the terminal if you have never used it before. Personally I prefer breaking big tasks into smaller, more easily achievable wins rather than trying to do everything all at once - start with the easy thing before moving on to the hard thing.

If you don’t want to think hard about choosing a DE and would prefer to skip this section, my tl;dr opinion for Windows users would be to start with a distro that has a KDE option and see where that takes you.

There are probably hundreds of options here, and lately it seems that it is becoming more common to see that a single distro will come with several different installer options that allow you to choose the DE you want up front, so it is worth having at least a general idea of some of the choices you might see. Without getting too far into the anatomy of a desktop environment, there are again really only 2 main DEs to be aware of, and then some (more or less) popular offshoots of those:

• KDE Plasma

Based on the Qt toolkit, this provides a feature-rich, highly customizable interface that will feel immediately familiar to Windows users. Honestly this is probably the best place to start if you feel overwhelmed by the sheer number of DE choices out there, because you can change pretty much everything about it to look and behave exactly the way you want. Some other notable members of the Qt family:

- LXQt: more or less a stripped down minimalist version of KDE that works well on older hardware

- Trinity: a fork of the older KDE 3.5 which aims to preserve this experience, maybe a good choice if you yearn for the glory days of Windows XP

• GNOME

Based on the GTk toolkit, this is a popular yet polarizing choice and the default for many mainstream distros such as Ubuntu and Fedora. It provides (compared to KDE) a somewhat minimal experience: by default there is no system tray, no task bar, and there are no desktop icons or widgets - basically just a clock/calendar and a control panel widget for accessing system settings are all you see on the desktop. Customization options are limited and many things you would normally do with a mouse are more easily done with keyboard shortcuts, but this allows for a pleasantly clean and simple look that doesn’t distract you from your work while still being powerful enough to do most of what you need a DE to do. This is my personal favorite so far, but there are quite a few other options based on GTk if the highly opinionated decisions of the GNOME developers rub you the wrong way:

- MATE: aims to preserve the design philosophy of GNOME 2, generally a simple and lightweight experience

- Cinnamon: aims to preserve the design philosophy of GNOME 3 (remember when I said GNOME was polarizing?), now a heavier and feature-rich experience similar to Windows

- Budgie: a heavier and more customizable “traditional” desktop experience, not a fork of any particular GNOME version but heavily relies on some of the underlying apps and components

• Others

Also GTk-based but started as independent projects completely separate from GNOME, these show up frequently in any DE discussion:

- LXDE: the spiritual predecessor of LXQt, which is the Qt rewrite of LXDE. A lightweight choice for older hardware

- XFCE: probably the most popular truly lightweight, minimal DE which is also a good choice for old or low power hardware

The choice of Qt or GTk is almost entirely insignificant, as apps built with either toolset will still work on “the other” DE. You don’t need to bother with understanding the difference between the two, it is only mentioned here because apps from a given toolset tend to be somewhat constrained to a certain kind of look and feel.

In the event you find yourself wondering why a specific app looks weird, doesn’t match the rest of your desktop theme (or rarely, has a bug that affects functionality), there’s a good chance it has something to do with these underlying components, so it’s good to know which components you’re trying to use.

Window Managers (WM)

It’s also worth briefly mentioning here that every DE uses a Window Manager, and hopefully this is not a surprise at this point, but the WM can also be changed. It’s also possible to use just a WM without any DE at all, although this is considered a setup for advanced users, and one which is usually keyboard-only with no mouse. This allows you to see and arrange the GUI windows that an app displays, but otherwise may not have any of the components of a “Desktop” that you would expect like a clock, file manager, a utility to change system settings, etc. Using just a WM gives you essentially a hybrid command-line-only system which can also display limited graphic elements like a browser window or a code editor. Just know that if you come across this term, what you are looking for as a beginner is a Desktop Environment, not a Window Manager.

Package Managers

Package managers are a significant departure from the way things work in Windows, and there is one at the heart of every distro. In a nutshell, a package manager is like the app store in Android or iOS devices, and much like the way you download apps from the app store on your phone, with Linux you download the programs you want to use from the package manager. If you really sit down and think about it, the way you install new programs in Windows is kind of weird and crappy - you google the name of a program and start clicking around on random websites trying to find a link to what you want, and often there are ads disguised as download links for the thing you’re looking for, or even worse, the link is a malware installer. Once you finally get the real installer for the program you want, you need to click through a bunch of menus to uncheck all the options to: sell your personal information to third parties; sign up for email lists; install browser plugins or God knows what else; and if you’re really unlucky, once you have done all that you will be rewarded with even more ads. In many cases you also still have to pay for the privilege of sitting through this ordeal in order to get a license to activate the features of the software you really wanted to use in the first place.

I’ll blame anyone as long as it’s not me

I’ll blame anyone as long as it’s not me

This is where that open source philosophy I mentioned earlier comes into play. Linux has none of these problems - you can essentially open a terminal, type in a command resembling “download my-desired-program” and… begin using your program a few seconds later. That’s it. Everything is free (and ad-free) and the repository of software you can download is curated by the distro maintainers, so you can be sure you’re downloading exactly what you think you’re downloading. You don’t need to download a .NET framework or C++ redistributables or try to figure out why some random .dll file is missing, because the package manager ensures all the components required to run a program are also installed alongside it. Furthermore, the source code of everything you can download is open for inspection by anyone, so you can really be 100% sure that apps don’t come with any hidden malicious behavior (and even if you personally are not reviewing the code, rest assured that thousands of nerds around the globe are).

Many distros now even provide a sort of GUI app which allows you to install apps just by clicking, much like any other app store, although these tend to be quite limited in my experience and you are going to end up needing terminal commands regardless if you really want to do work that can’t be done in a browser. And while in most cases everything you need will be in the package manager, it IS still possible to download and install software “from random websites” in Linux, but that generally must be done in the terminal, and it requires a bit of understanding about how your package manager works (unless you want to get into building software directly from the source, which is another story for another time).

In order to find the right commands, you first need to know which package manager you’re using. Unlike desktop environments, it’s almost always possible to tell which package manager you’re using just by knowing which distro you’re using or vice versa. Much of the philosophy of a distro manifests itself through the package manager, in the form of the distro maintainers deciding (or not deciding) which packages are available there and how frequently they are updated. This is to say, it would generally be really difficult (although not entirely impossible!) to switch from one package manager to another within the same distro because of how much the underlying operating system relies on the package management system.

With all that being said, the most common package managers and their associated package formats are listed below. Note that in all of these cases, the name of the package manager is also the name of the command used to run it - how convenient!

- apt (Advanced Package Tool)

- uses the “.deb” package format

- uses the

dpkgcommand behind the scenes to perform low-level interactions with .deb files - used by Debian and most of its derivatives (Ubuntu, Linux Mint, Pop!_OS, Kali Linux, Raspberry Pi OS, and many more)

- dnf (“DaNdiFied yum”) or yum (“Yellowdog Update Manager”, old version but interchangeable with dnf)

- uses the “.rpm” package format

- also uses the command

rpmbehind the scenes to perform low-level interactions with .rpm files - used by CentOS Stream, Fedora, Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Rocky Linux and others; common in enterprise server environments

- pacman (hopefully the naming convention here is self-explanatory)

- generally uses “.pkg.tar.zst” format, although you may see other “.pkg.tar.*” formats

pacmandoes not have a lower level helper command - one command does it all!- used by Arch Linux and its derivatives (Endeavour OS, Garuda Linux, Manjaro, SteamOS, and many more)

- honorable mention: zypper

- used exclusively by openSUSE and SUSE Linux Enterprise

- also uses

rpmand .rpm files like dnf/yum, but zypper/SUSE .rpm packages are most likely NOT interchangeable with dnf .rpm packages - be careful!

Notice that it seems to be a common practice to have both a higher level interface (like apt) and a lower level interface (like dpkg) for working with packages. You could think of this sort of like a vending machine: what you really want is a coke, so you press the coke button, and a coke comes out. This is what apt handles for you, it’s presenting the menu of buttons which can be pressed. Behind the scenes, dpkg is the program controlling which motors inside the vending machine need to turn and how far or for how long each one needs to turn in order to put your desired product in your hand. You could eventually figure out how to get the same result as pressing the coke button on the outside using this low level program, but it’s much nicer to just press one button when there’s no need to specify all the gritty details. So, in most cases you will use the high level interface to do stuff, but it’s worth being aware of this association here because it’s also not uncommon to see tutorials out there which use the low level commands instead.

You might also come across mentions of things like Snap, Flatpak, or AppImage - these are all attempts at self-contained app “sandbox” environments which bypass package managers entirely by including all the required dependencies in a single package, which in theory means that the exact same version of an app can be installed in any distro regardless of the package manager or environment-specific unknowns. In theory a great idea, but in practice there are downsides to this approach as well, namely that there will be some additional storage space and/or CPU overhead required to run these apps. There is a time and place for everything and I would say the best use of these formats is to install something not provided natively by your package manager - otherwise, you are probably better off at least making an attempt to get the native version working first.

The Foundation of Doing Stuff

Now that you’ve seen some of the big ideas that differentiate Linux distros from each other, let’s look at some concepts that are generally the same in every distro (but very different from Windows) which are really crucial to developing the fundamental understanding of why things are the way they are in Linux and how to navigate around them.

Filesystem Roots and Paths

In Windows the storage space on your computer is organized by “drive letters” accessible from My Computer - typically the operating system and all your programs will be installed on the C drive, and any additional drives (hard drives, USB flash drives, SD cards, CD/DVD drives, network attached storage, etc.) will have an additional drive letter from D to Z. And a fun fact for anyone born in this century: drives A and B were historically reserved for floppy drives, which is why your hard drive always starts at the letter C and not A.

The drive letters act as the “root” of each drive, the highest organizational level at which files and folders can be created. File paths always start with the root, for example C:\, and below that you have files or folders for organizing stuff: C:\Program Files for your installed programs, C:\Windows for operating system files, etc.

In Linux, there is no such concept of drive letters. Instead, there is only one logical root for the entire system, which begins at the top-level path / (notice the path separator in Linux is ‘/’ and ‘\’ in Windows) and is not strictly associated with any physical device. This begins to make much more sense in the context of servers and supercomputers, where you may not only have hundreds of drives, you may also have hundreds of separate computers that are connected to each other, acting as one big computer and sharing those drive clusters. In this case you would find yourself quickly running out of letters, and not wanting to think about which physical drive or machine a file is associated with. Also, everything else (not just drives, but all hardware connected to your computer) is represented as a file somewhere under this root. More on that in just a second, but first some additional noteworthy differences:

- Paths are case sensitive in Linux (you can have 2 different folders called downloads and Downloads) while in Windows they are not (downloads and Downloads are the same folder)

- Windows paths and filenames often contain spaces. Linux filenames can contain spaces but this is inconvenient and frowned upon since the space character is also used to separate command line arguments

- Windows paths and filenames cannot contain many special characters such as

<>:"\/|?*. In Linux you can name files with almost any character other than an unescaped/, even UTF-8 characters like emojis - File extensions like .exe or .txt are important in Windows. In Linux the file extension has less significance and is not necessary at all, but they are still often used as a hint to what the file contains or which program should be used to open it

- Some applications may have trouble with path names longer than 260 characters in Windows, in Linux this limit is more easily configurable and often set to 4096 by default

- Windows has “shortcuts”, most commonly on the desktop, which are a specific type of file (.lnk) that can open the location of another file. Linux has the roughly equivalent concept of “symbolic links” or more commonly “symlink” at the command line level which creates an alias or pointer from one file path to another

You will probably also notice that the top-level folders in a Linux system have cryptic names such as /bin, /etc, /mnt rather than human-readable ones like C:\Program Files, C:\Users, C:\Windows, etc. But there is a method to this madness called the Filesystem Hierarchy Standard which describes what you should expect to find in each of these folders.

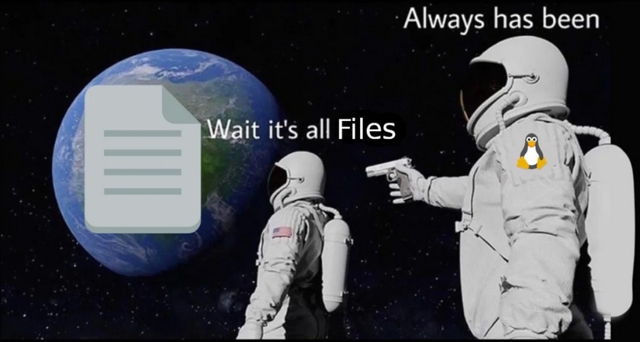

Everything is a File

Absolutely everything in and around your computer is represented as a file somewhere in the filesystem in Linux. Folders are files. System settings are files. Network interfaces are files. Processes are files. Even your CPU, monitor, and keyboard, believe it or not, also files. The “everything is a file” philosophy takes some getting used to, and in fact it also explains a lot about why Linux is (or more recently, was) so heavily reliant on the command-line. When everything is a file, it’s very easy to represent everything (data, resources, commands, etc.) as a text stream into or out of a file. By abstracting everything to file operations (open, read, write, close), there is only one standard set of tools and a single interface through which pretty much everything in the operating system is accomplished. For example, the output of some program which was supposed to be displayed on the screen could instead be just as easily saved in a file on your hard drive, or sent to another device across the network. That’s possible because your screen, hard drive, and network are all just files which use the exact same input and output system, and it’s trivial to choose which file a program will output to.

In Windows the idea is “everything is an object”. Every object type has essentially its own API that the operating system can use to interact with that object, and you interact with this object indirectly by obtaining a “handle” or reference to that object through the API. This model lends itself well to graphical user interfaces, because a text-based interface becomes significantly more complicated when screens, hard drives, network interfaces, etc. all use a different interface and can’t interact with each other directly or share a common toolset. Essentially Windows started as a powerful GUI which had a command-line interface bolted to it later, while Linux started as a powerful command-line interface which had a GUI bolted on later.

Ownership and Permissions

Linux has a relatively simple file permission system, although the much more sophisticated Windows permission system rarely needs to be touched by anyone outside of a corporate IT department, so there is a good chance you have never given much thought to this topic anyway. I won’t explain it in great detail here, but would highly recommend looking to something like the Red Hat Blog for an in-depth explanation of how to interact with the file permission system in Linux because it is an important topic. But for the short and sweet version, there are essentially three ownership classes in Linux:

- User (that’s you)

- Group, a named list of one or more users

- Everyone, that is, any user anywhere who is not explicitly mentioned by a user or group ownership definition

Every file is considered to be owned by 1 user (usually the creator of the file) and 1 group, effectively granting the ability to extend ownership to multiple users if necessary. Each ownership class also has 3 permission attributes which can be set independently:

- Read

- Write

- Execute

These are exactly what they say they are: the ability to read the file contents, the ability to write or modify the file contents, and the ability to execute the file contents as a script. The 3 groups and 3 permissions can be used in any combination, so for example a file containing some program could have the full permissions read, write, execute for the user that owns the file, while any users belonging to the group that owns the file could be limited to only reading or executing the file, and finally everyone else can be restricted to only executing the file, without being able to read it or change it in any way. While there are special extended permission attributes and things like Access Control Lists that allow for more granular control of who can do what with which files in enterprise environments, these are far beyond the scope of this article.

If you find yourself wondering Why does it matter? Why do I need to know this? consider that the Linux file permission system is a remnant of the time before personal computers were really a thing. Before the PC - a time long before I was born that I have only heard about through my parents - there were “mainframes” (servers) and “terminals” (clients), basically just one big computer that everyone in a university or office building shared through the use of distributed terminals, which in turn were little more than a screen and keyboard with long cables that provided a means of interacting with the mainframe. Today Linux still operates on the assumption that the computer is a server (which quite frankly is still a very common use case, see the internet) which will be accessed by multiple users simultaneously. So the ability to control file access at the individual user level is much more important than it is in Windows, which is primarily built around the assumption that everyone will have their own separate computer and nobody will ever have a reason to connect directly to yours.

File permissions only apply while on the computer that holds the file - if you can read or transfer the file to another computer, then the owner of that machine will be able to change the content, owner, and permissions as they see fit, so these permissions do not necessarily provide bulletproof security that will prevent someone else from uncovering the contents of a file.

A noteworthy caveat to this permission system is the super user, which is for all intents and purposes equivalent to the “Administrator” in Windows, just a much more extreme version. The super user is granted all permissions on all files, which is equal parts terrifying and dangerous. There is a joke commonly posted online which goes something like “to save hard drive space after installing Linux, make sure you delete the French language pack with this command:”

Do not do this

Probably sounds like reasonable advice to the uninitiated, but this is an extremely destructive command which will attempt to irreversibly delete everything on all devices mounted under the filesystem root, which really means everything including all hard drives, USB flash drives, network file shares, and yes, even the operating system. So in short, don’t run commands you don’t understand - with great power comes great responsibility.

Finally, no Linux primer would be complete without mentioning the sudo command - I guess I sort of already did, but this is short for “super user do” and gives the subsequent command the ability to run as the super user, which means it will ignore all permission and ownership settings. Prefixing a command with sudo is roughly equivalent to “Right click -> Run As Administrator” in windows, or bypassing the User Account Control popup that asks if you’re really sure you want to allow this program to make changes to your computer. Really, it’s more like releasing the safety from a gun and pulling the trigger, so again, pay attention when running any commands that start with sudo.

Command Line 101

Last but not least, the almighty command line. Up to this point I’ve at least made an attempt to keep things simple without getting too far into the weeds, but in this section I expect you probably will not get everything on the first read through. Let’s just go ahead and call this like it is because there is really no other way around it: becoming proficient in the use of the Linux command line is a somewhat difficult and probably painful process that is going to require a good bit of dedication and patience on your part. For lack of better words, it requires a lot of ass-in-seat time fumbling your way around in order to develop the muscle memory required to be able to get anything done without having to look up how to do it every time. So, I would encourage you to come back and read this again at some point in the future because it will probably make more sense the second or third time.

Ubuntu provides an excellent tutorial for getting started with the basics. But there are still a few points that I think every guide out there could expand on (if it hasn’t missed them entirely), and some things which in my opinion would have been nice to know in the beginning rather than having to experience them as sporadic ‘aha’ moments popping up months or years later.

• Terminals vs Shells

The terms terminal and shell are often used interchangeably, and I’m not here to rain on your parade and say that you can’t interchange them, but there is actually a difference between the two which is important to understand if you ever want to (or have to) use a different version of one or the other. One would imagine this should be a question that is easy to answer in plain english, but the top Google results for any variation of “terminal vs shell” seem to provide information which is at best overly pedantic or difficult to understand and at worst just downright incorrect. So I’ll try to lay it out in just one sentence to set the record straight: A terminal is a GUI application (think Excel or Visual Studio) which provides access to a shell, and a shell is a text-based program which provides an interface to the operating system via a set of text commands (think about the list of formulas you can write in an individual spreadsheet cell and how the results are calculated, or scripting in interpreted languages like Java or Python).

To put that another way - the terminal is the name of the program that will be displayed on the screen (such as konsole if you are using KDE, or gnome-terminal if you are using GNOME) and the shell (most commonly bash, could also be fish, ksh, tcsh, zsh, etc.) is the name of the command interpreter and scripting language that determine which commands you are able to write.

The pedantically correct term for terminal here is ‘terminal emulator’ because a ‘terminal’ as mentioned earlier is a hardware device and not an application, but hear me out: Life is too short for this argument and nobody cares, just say terminal.

As for shells, bash is the de facto standard shell in Linux - even if a distro ships with a different default shell, bash is almost always included alongside it. Mac OS uses zsh however (if you were not aware, Mac OS is derived from FreeBSD which also evolved from UNIX as Linux did, and they have a lot in common), so there is a case to be made for branching out and using different shells at some point in the future. For now, just assume you’re going to be using bash because it is everywhere.

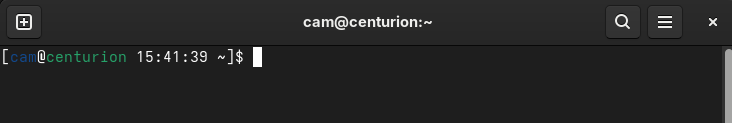

• Don’t copy the dollar signs

Thankfully this seems to be dying out, but it’s still not uncommon to find shell commands written in tutorials and forum posts like this:

1

2

3

$ sudo apt update

$ sudo apt upgrade

$ sudo apt install package1 package2

The $ is the end of the command prompt, not part of the command, and this is often not immediately obvious to new users copy and pasting stuff from the internet. This is, however, actually an important signal that you should be running these commands as a normal user and not the super user, as that’s typically what you see when opening a terminal:

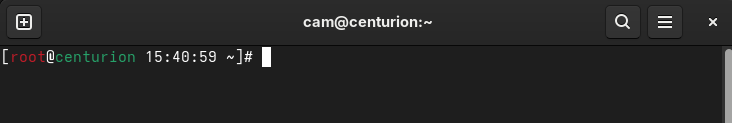

You might also see the commands written like this instead:

1

2

3

# apt update

# apt upgrade

# apt install package1 package2

Notice the # instead of $ - this means the command should be run as the super user, which means you probably need to add sudo to the front unless this is going to be part of a script which will be run with sudo later. An example as the super user, which you can see now ends the prompt with # instead:

• RTFM

Reading is an unescapable fact of life when it comes to learning Linux, and you will be doing a lot of it. Fortunately most of what you need to read is already built into the operating system and doesn’t require internet access. At the beginning of this article is a joke about a hypothetical Linux user’s hostility towards noobs, so you may have been hoping not to hear this, but at least making an attempt to read the manual or the wiki for your distro IS a solid first step to doing anything. Online Linux communities are (for the most part) less hostile than they were a few years ago, but whether they are or aren’t, at the end of the day Linux is about choices (even if not all of them are made by you), and you should be prepared to spend some time understanding what choices are in front of you and what choices led you to this point.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not saying you should not ask for help, I’m saying you should not just go blindly asking for someone to tell you what button to press without having even the slightest understanding of where you are, how you got there, or what it is you’re actually trying to accomplish, and then get upset because nobody else wants to do your homework for you. It’s exactly the same as if you’re going to see a doctor: you should come prepared at the very least with a list of symptoms and any medications you’re taking; or if you’re taking your car into the shop, you should be able to describe the year, make, and model of your car, any funny noises it’s making, and your maintenance history. It’s just common courtesy that you don’t barge into somebody’s office and say “something’s not right, now tell me what it is” without providing any context, and Linux is no different.

That being said, any time you find yourself copy and pasting commands from somewhere and don’t know what you’re looking at, it’s generally good practice to spend a few minutes reading the man page first (that’s man as in manual, not men, but it will still be hilarious at some point in the future) to try and get an idea of how the person or LLM who wrote the command was able to come up with it in the first place. You can find this by typing man <command> for any command you want to know about. You can also generally always type <command> --help to get syntax hints and a short summary of available options, while the man page provides all the gory details. For the really long ones, you can also search online for ‘<command> man page’ to read it in a browser instead of a terminal.

In addition to all the built-in commands and your installed programs, there is a man page for your package manager, and even a man page for the man command, so man man is the one man page to rule them all. While not immediately obvious, there is also a man page for the shell you’re using, so assuming you’re using bash, you can simply type:

1

man bash

to view the manual for bash itself. In the event man isn’t installed by default it’s usually at least available from the package manager.

The bash manual is quite long and dense, and to be honest I have not read most of it because I learned a lot of it “the hard way” before ChatGPT was a thing - by scouring stack overflow posts for the meaning of commands I found in other stack overflow posts. Looking back, I could have saved a lot of time by learning how to read the manuals instead, basically cutting out the middle men and going straight to the source of truth rather than having it filtered through the minds of people who may or may not have any idea what they’re doing. But anyway, the bash man page does explain in great detail the answer to almost any kind of “how/why did they do that?” question you could have when coming across bash commands in the wild. There are also quite a few gems to be found in there if you’re willing to attempt it as a beginner, namely:

1

compgen -b

This command will provide a list of every command which is built into bash itself (that is, not commands which are part of the operating system or its installed programs, but the commands that will always work in any distro anywhere you find a bash prompt). Many of the same commands will be available in shells other than bash, which is to say, reading the man pages for the commands in this list will give you a really solid understanding of what you can do in a terminal, a level of understanding that will likely even transfer outside of Linux to other Unix-like environments such as Android and Mac OS.

If you sit down in front of any random Unix-like device and don’t even know what shell you are in, you can also generally do this to find out:

1

echo $0

• Every command is the same

For the most part, everything you can type in the terminal is going to follow a very similar pattern that usually looks something like <command-name> [-flags|parameters] {subject}. Maybe not always, as there’s nothing which says the author of the tool has to do it this way, but the vast majority of programs out there behave this way. In many cases there may simply be a command with no flags and no subject, for example pwd which prints your current working directory. Flags will sometimes have their own parameters, as in the example ping -c 1 127.0.0.1 where the flag -c (for count) has the parameter 1 and the subject is 127.0.0.1 - all together in plain english, send a ping request to your own computer 1 time. The ping command does not require any flags, but without -c it will continue indefinitely. However, in this case if there is no subject, the command will give you an error message like ping: usage error: Destination address required.

Most commands will allow you to combine flags that don’t require a parameter into “one big flag”, for example:

1

2

3

ping -A -L -n -4 -v 127.0.0.1

#could more easily be written as:

ping -ALn4v 127.0.0.1

I have no idea what this does, just a random selection of flags from the man page. Usually the flags and subject can also switch places without hurting anything, so these two are exactly the same command:

1

2

ping 127.0.0.1 -c 1

ping -c 1 127.0.0.1

If a command takes a subject, it’s usually used to specify the thing that the command is operating on - that is, the thing which will be impacted/changed/created/used by the core functionality of the command, while flags generally represent options for things like output formatting or other behavioral choices. This may take the form of a path/filename, an IP address, a search pattern, or something else entirely. In many cases the subject can also be a list of several subjects, for example mkdir folder1 folder2 folder3 will make 3 new folders with those names - there are many possibilities here which will be described in the man page.

Where things start to get really tricky is that the subject can also be another command which has its own flags and subject, and successive commands can also be chained together indefinitely with things like pipes and output redirection (more on those at the very end). Consider sudo apt update - the command is sudo with no flags, and the subject is everything after it: the command apt which in turn has the subject update.

• Text Editors and Keyboard shortcuts

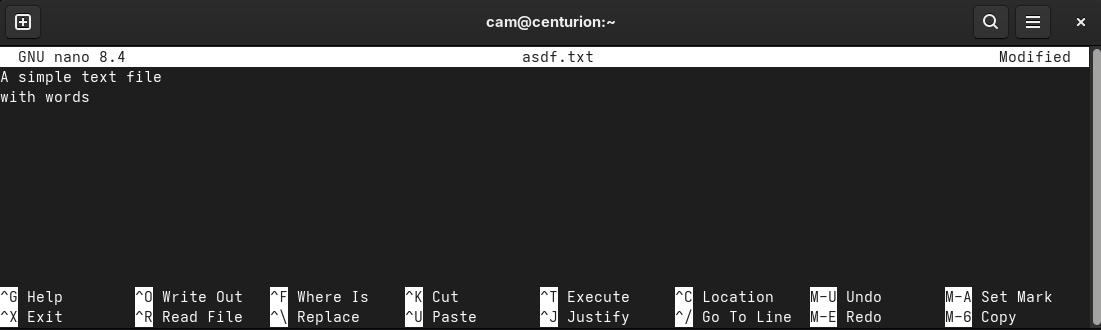

The familiar Ctrl-C / Ctrl-V, Ctrl-F, and Ctrl-Z from Windows generally work in Linux desktop environments as well, however they don’t apply to anything you will do in the terminal. Any time you need to edit system configuration files, you generally need to open them using a command like sudo <text-editor> <file-path> because clicking on files in the file explorer will open them with something like kate in KDE or gnome-text-editor in GNOME as your regular user, which means you won’t have permission to save the file (not to mention you may not even be able to view some system folders in the file explorer as a regular user). You can just add sudo to your GUI text editor command, but if you need to do something on a headless or remote system and it’s not possible to use the GUI app, it’s good to know how to do this the old fashioned way. There is an easy-to-use terminal text editor called nano which is available from every major package manager and installed on most systems these days by default. Many people will tell you to learn the more powerful (and also much more difficult) vi or vim because it’s going to be available on basically everything ever built since the ’70s, or that you need to learn emacs which is almost a second operating system that runs entirely within the terminal - that’s up to you, personally I think if you can’t do something in nano it’s time to open a VScode remote session and save the brain space that would be used for all those keyboard shortcuts for something more important.

nano is kind enough to show you some commonly used keyboard shortcuts are every time you open a file (note that the bigger the window gets, the more shortcuts that will be displayed):

Although at first glance this probably doesn’t mean anything to you, the short and sweet version which you may find is relevant for a few other command-line tools is that ^ stands for Ctrl and M- stands for Alt. So for example if you want to copy and paste something, you first need to move the cursor (with the arrow keys) to the start point, press Alt-A to set your mark, move the cursor again to the end of your selection, then press Alt-6. Finally you can paste with Ctrl-U, and when you’re done exit with Ctrl-X (which will also then ask if you want to save the file if you made any changes).

If you think these shortcuts are weird and make no sense, I agree with you. Fortunately you don’t need to spend a lot of time thinking about them, because these are unique to nano and they are already displayed for you every time you use it. If you really wanted to you can also change them by editing the /etc/nanorc file, but this is probably more trouble than it’s worth if you ever have to work with any Linux devices other than your own computer.

Some other really useful keyboard shortcuts that generally apply everywhere else:

- Copy1: Ctrl-Shift-C (if you make a selection with the mouse first)

- Paste1: Ctrl-Shift-V

- Exit: Ctrl-C - interrupts (kills) the program currently running in this terminal window

- Stop: Ctrl-Z - suspends the currently running program and gives the input prompt / keyboard control back to you

- from this state you can type

bg(background) to let the command continue running in the background fg(foreground) brings the background task back to the foreground- alternatively you can add

&(with the preceding space) to the end of any command to start it in the background

- from this state you can type

- Auto-completion: Tab - extremely useful for long file/folder names, commands, and more, you can just type the first few characters and then press tab to fill in the rest automatically

- Command History:

- previous command: Up arrow - cycle through previous commands with the up and down arrow keys

- search history: Ctrl-R - when you can’t remember that really long command from 3 days ago but need to do it again, start typing any command after pressing this to search through and provide auto-complete options for your command history

- Find (in man pages): press ‘/’ and start typing, press enter to highlight all occurrences of the search pattern

Again, this is just within the terminal. In most GUI apps (browsers, text editors, or whatever) your usual Ctrl-C / Ctrl-V, Ctrl-F, Ctrl-Z, and others will still be the same as in Windows. You may have different keyboard shortcuts with a shell other than bash and there are many other shortcuts as well. You should be able to use stty -a or man stty to find out what is possible.

One final note on keyboards: the ‘Windows key’ is called the ‘Super’ or ‘Meta’ key in Linux, and once you become a serious Linux user you are legally required to exchange the keycap (or the entire keyboard) with one that has anything other than a Windows logo for this key, otherwise the internet police will make fun of you.2

• What the $&!> are all these symbols

The last point I want to make is probably the scariest part of learning the command line, because sooner or later you will find yourself trying to wrap your brain around something that just looks like a cat walked across the keyboard, like this:

1

2

3

4

find . -type f -name "*.txt" -print0 | while read -r -d $'\0' filename; do

word_count=$(wc -w < "$filename" | awk '{print $1}')

echo "File: $filename --- Word Count: $word_count" >> ~/text_file_word_counts.log

done

Bash uses a ton of symbols and shorthand which make it possible to write really complex expressions on a single line. While this will appear overwhelming if you don’t know how to read it, this is actually a relatively simple command which finds .txt files inside the current folder (including all subdirectories), and then creates a log file in your home folder which lists the name of each file that was found and how many words it contains. A contrived example which probably doesn’t sound all that useful, sure, but this has a ton of concepts packed into a small space.

I will leave the exhaustive explanation of how this works as an exercise for you to uncover on your own, but here’s an overview of the important ideas:

- Multiple commands:

find,read,wc,awk,echo(check the man pages!) - Pipes: the

|character, this feeds the output of one command into the input of the next command instead of displaying it on the screen - Loops: the bash-flavored

whilestatement which in this case willdothe subsequent commands for every filename found with thefindcommand - Variables: for example

filenameandword_countcan store information that will be re-used later - Command substitution: the

$(...)to the right ofword_count- this construct executes the commands inside the parentheses, and then replaces the entire$(...)with the output. As an example, if there is a file which contains 60 words, the result of this command substitution would simply beword_count=60 - Parameter (or variable) expansion: you can use the stored value of a variable by putting a

$in front, e.g.$filenameor$word_count - Input/Output redirection: the

<and>>- here<is providing the filename as input to the wc command, while>>is providing the output of the echo command to the log file in your home folder - Tilde expansion: similar to the

aliascommand which is more generic, this built-in function of bash replaces~with the location of your user’s home folder (basically ‘My Documents’ in Windows)

If you’re wondering how could anyone possibly know all of that? man bash - all of these concepts and more are explained in excruciating detail there.

That’s all for now, and if you made it this far, thank you for reading! If there is any way I can improve this article please leave a comment or contact me directly.

-

These work in many terminals but there may be a different key binding, look for a “settings” menu in your terminal window if it doesn’t work ↩︎ ↩︎2

-

They will have no way of knowing what your keyboard looks like, but you will still have to find a way to sleep at night knowing it’s the wrong button ↩︎